Understanding and Managing Rumination in Children

Rumination is a mental habit that involves repetitively thinking about negative events, worries, or feelings. Rumination happens when a child repeatedly dwells on the same distressing thoughts, often without finding a resolution. While occasional reflection can be helpful, rumination often traps children in a loop of negative thoughts that can impact their mood, self-esteem and academic performance. It can lead to feelings of sadness, anxiety and a sense of helplessness.

Signs of Rumination in Children:

- Repetitive worries or negative talk: Constantly bringing up the same worry or self-critical thought, even after reassurance or resolution.

- Difficulty moving past mistakes: Struggling to let go of small setbacks or mistakes, replaying them in their mind and talking about them frequently.

- Trouble sleeping due to ‘overthinking.’

- Increased anxiety or sadness: Appearing more anxious, withdrawn, or sad, especially after a difficult event or even a minor disappointment.

- Low mood or withdrawal from activities they typically enjoy.

- Physical symptoms of stress: Headaches, stomach aches, or trouble sleeping, which can stem from persistent worry.

- Excessive need for reassurance: Frequently asking for confirmation or reassurance about things they are worried about, often without feeling satisfied by responses.

- Avoidance of new situations or challenges: Avoiding activities that could lead to mistakes or discomfort, especially if they are afraid of repeating past situations they have ruminated on.

- Difficulty focusing: Struggling to concentrate on schoolwork or activities because their mind is often preoccupied with negative thoughts or worries.

How to Help Your Child Break the Cycle:

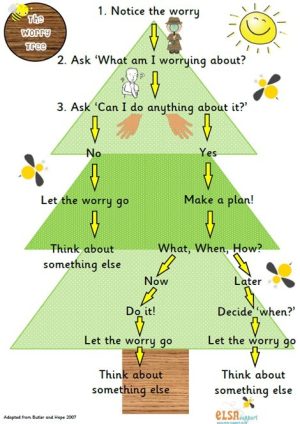

- Teach problem-solving skills. Help them break down their worries and think through actionable steps. The following recipe adapted by Butler and Hope might help:

- Letting the worry go, and thinking about something else might, however, be much easier said than done. The following strategies could help with this:

- Encourage distraction techniques. Suggest and support them to engage in activities they enjoy, like playing a sport, drawing, or reading, to redirect their focus.

- Redirect their attention externally rather than internally. Becoming mindful of the present moment by using their senses (sight, sound, touch, smell, taste) can help them to “get out of their minds and back into their lives.”

- Mindfulness practises can help children understand the fleeting nature of thoughts and can assist them in accepting their thoughts as they are. For example, focussing on the breath, or doing a body scan can help children to bring themselves into the present in a way that will make thoughts of the past or the future less noticeable.

- Remind them that thoughts are not facts and that our thoughts are often not true. Normalise irrational thoughts by providing some examples of your own irrational thoughts at times.

- Promote positive self-talk. Encourage phrases like “I can handle this” or “This feeling will pass” to help counter negative thoughts.

- Model healthy thinking patterns. Show them how you address concerns in a balanced way, focusing on solutions rather than the problem alone.

- Postpone the worry. Support them in saying to themselves that they are not going to engage in this worry right now but will engage in this worry later. They could even make a list of specific worries that they will worry about later. Then, set aside a dedicated worry time every day at a set time for the specific purpose of worrying, e.g. 15 minutes at 6pm. Allow them to worry as much as they can for the whole dedicated time. They could also write down or draw their worries during this time. Some children might find it useful to put their worries into a “worry box”, and others might find it useful to tear up the page with the writings or drawings of the worries afterwards.

- Research finds that having a self-compassionate mindset is tied to less rumination, so support your child in treating themselves the way they would a good friend and to be kind to themselves. Also model this to them in your own self-talk and self-care practices.

- Hundreds of studies show how physical exercise, in general, can be helpful for reducing rumination. Even engaging in a single session of moderate exercise has been found to reduce rumination.

- Being outside in nature has also been proven to reduce rumination, so put on those hiking boots and go for some therapeutic walks in nature with your child.

- Practicing gratitude can be a powerful tool to help children break the cycle of rumination as it redirects focus, promotes positive emotions and builds resilience. Simple gratitude practices can include:

- Gratitude journals: Encourage your child to write down three things they’re grateful for each day.

- Gratitude jars: Keep a jar where they can add notes about things they appreciate. Over time, they’ll have a collection of positive memories to revisit.

- Gratitude conversations: Set aside a few minutes during family time to share what everyone is grateful for. This reinforces the habit and models gratitude as a family value.

If rumination is so problematic that it’s hurting your child’s health, relationships, or ability to engage with life, it may be a sign of a more serious condition. In that case you’ll want a professional, like a psychologist or counsellor, who can provide guidance for letting go of troubling thoughts and moving into healthier thinking patterns. Your GP can review your child and offer recommendations for specific support providers.

Other Support Services:

- Headspace has centres in Narre Warren, Pakenham, Dandenong and Frankston, and can be called on 1800 367 968

- Kids Help Line offers free 24-hour telephone support or online chat for children on 1800 55 1800 or www.kidshelpline.com.au

- eHeadspace offers free telephone or online chat support on 1800 650 890 www.eheadspace.org.au

- Psychologist

387

387